The Innovation Enthusiasm Gap

Getting new innovations launched within companies of any significant size typically requires buy-in from a number of different people and groups around the organization.

And moving towards a “culture” of innovation that the most successful companies create definitely requires that there be a critical mass of people with common understanding of the value of innovation.

Different Attitudes Towards Innovation

In any given enterprise there are generally many people who are hungry for the excitement of innovation and at the same time there are often many people who are resistant. Innovation, after all, inherently means change. And while change is viewed by some as exciting, challenging and fun, others view change as risky, scary and something to be avoided wherever possible.

Understanding how to segment your key stakeholders at all levels of an organization based on their appetite and attitude towards change is very helpful in devising a plan to “bring along” as many people as possible on the innovation bandwagon. All people are unique and hold certain beliefs and attitudes for a variety of reasons including their personality, past experiences, and reward constructs. But we’ll talk about one high level trend that we have found to apply in most cases regarding how to gauge the likelihood that people will have initial enthusiasm for innovation based on their level in the organization. This is not the only way of slicing the onion to predict who will favor vs resist innovation, this is just one model, but it’s the one we’ll focus on in this article.

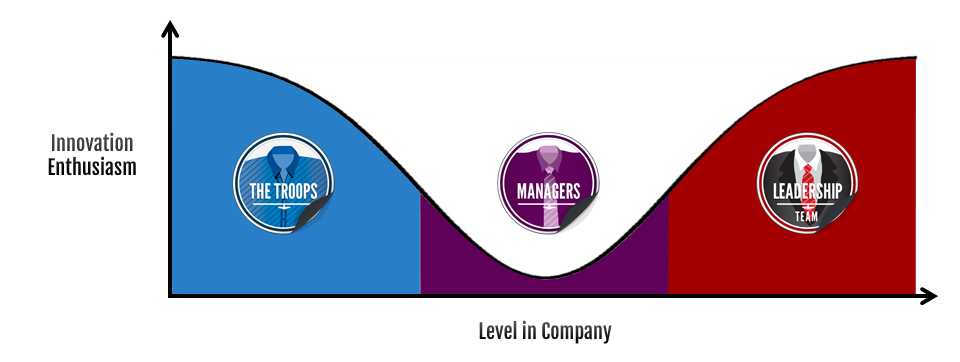

The Inverted Bell Curve

While we have no quantitative research to support this, we have generally observed an inverted bell curve trend as it applies to “Innovation Enthusiasm.” Let’s consider three basic groups:

- The company leadership team: Primarily the CEO, but also the other members of the leadership team (CFO, COO, COO etc) who are held directly responsible for the company's success.

- The "troops": The bottom couple of tiers of the organization that typically make up 90% of the employees

- The managers: Specifically the middle to upper level managers. These may be department heads, marketing executives, product managers — people who have achieved some level of status and success within the organization’s hierarchy but who are not at the top level.

So lets take these groups one at a time.

CEOs Like Innovation

The vast majority of CEOs of large enterprises recognize that innovation is essential to their company's success and consequently essential to their success and continued tenure as CEO.

Why is this the case? A CEO’s job is to grow a company. In most cases, A CEO whose company is not growing is a CEO who is soon to be fired. And growth almost always requires innovation. Why? Well let's be a bit simplistic and say there are two primary market conditions in which a company can find itself — a market which is not fundamentally growing and one which is.

In a market that is fundamentally not growing, the three main ways that a company can grow would be for it to:

- Out-innovate competitors so as to take their share

- Move into new product categories or businesses

- Acquire competitors

All three of these require some level of innovation. Number 1 is obviously about innovation. Number 2 requires a healthy amount of innovation around creation of new capabilities. And even #3, the seeming least innovative of the three, still usually requires innovation from a scale management perspective.

In a market that is fundamentally growing, sitting back and riding the "rising tide" is not necessarily the key to growth. Innovation is also critical for a company to grow in the midst of a strong market. Successfully riding the rising tide requires innovation. Why?

- Substantial scaling requires innovation - As markets increase in size, a company may find that in order to take full advantage of the scale of the opportunity they need to be able to serve 2x, 10x, even 100x the customers or orders they did previously. That level of scaling generally requires a substantial change to how business is done. Apple has had to be just as innovative in their supply chain and distribution approach as they have had to be with their product development in order to capitalize on the success in the growing market for mobile devices.

- Growing markets attract disruptors - If the market demand for a product or service is surging, that tends to attract investment and competitive innovation. If the market is growing but a competitor out-innovates you, you might find yourself shrinking even though the market is growing. Consider Research in Motion.

So a CEO has every reason to like innovation. Does a CEO have any reason to fear innovation? Not much. Innovation isn’t always successful, however most boards are far more patient with a CEO who is innovating and not finding success than they are with a CEO who isn't innovating at all. Furthermore, even unsuccessful innovation gives a CEO something to tell his board and investors to keep them optimistic about the future, so even innovations that are unsuccessful in the market can, for a while at least, keep a stock price up which is, after all, a CEO’s main performance metric.

The Troops Like Innovation

We’ll call the 90%+ of employees of a given company, the "troops”. While of course nothing is absolute, troops, on the whole, tend to like innovation. Why?

- They want the company to be successful - They can see that changing with the times and bringing new products to market will help the company. They take pride in the brand and they know that financial success and growth means job security and raises, and that their long term job security will be in danger if the company doesn't keep up with the times.

- It can help them serve the customer better - Troops who face customers directly most of the time want to do their job as well as possible since part of their job satisfaction can be the direct and immediate feedback they get when interacting with the end-customers.

- It creates opportunity - For ambitious people lower down in the organization, change creates new needs and new opportunities which could accelerate their rise.

- Its exciting and interesting - Lots of jobs are boring. Change creates interest.

There are certain types of change that can be threatening to the Troops; such as innovation via overseas outsourcing or automation that eliminates employees, so those are exceptions. There definitely are also members of the troops who tend to fear and resist change as a first reaction, however at most companies these are the minority. Properly communicated innovation initiatives that don’t have an obvious or direct threat to employees job security is generally embraced by the majority of the troops.

Managers Don't Really Like Innovation

So if The CEO’s like innovation, and the troops like it, whats the problem? You have both the top leadership of the company and the overwhelming majority of the employees ready to embrace innovation, surely that should be enough, right? It’s not. We see over and over again CEOs who feel stuck because they are asking their “people” to innovate and its just not happening. What we find at many companies is that despite being encouraged by the CEO and top management, most middle and upper-level managers have limited reasons to be motivated to truly innovate in a dramatic way. Why is this the case?

Change creates risk. Middle and upper-level managers have the most “stake” in the status quo - they have the most to lose. Middle and upper-level managers tend to own processes and products. When new processes and products arise to potentially replace their existing fiefdom, managers will often do their best to ensure that they wind up with the same scope of responsibility, the same budget and the same number of direct reports. While its possible for managers to move up in a new order, very often a “bird in the hand” mentality among managers encourages a stance which is about defending the status quo and supporting “innovations” which inherently work within the existing structure. Ultimately, this often means only very incremental innovations.

One might think that middle and upper managers have the same loyalty to the company and shared interest in the company’s overall success, but in our experience this is not quite so. Individuals generally rise to these ranks because they are fairly savvy and that savviness generally extends to the recognition that their personal career success is not necessarily tied to the company overall. For example a product manager with a successful product at a company which overall is going down the tubes can, at the right moment, jump ship and leverage their demonstrated track record of success. However an individual who becomes marginalized by change at their current company (or simply winding up with reduced responsibilities), while they certainly can still move to another position, is all of the sudden playing defense.

Furthermore, that mindset of innovation “within the current structure” is then telegraphed to their team members. Its common for the troops to realize that the CEO wants dramatic improvements based on his communications, however if lower level employees also perceive that the head of their department is looking to not rock the boat too much, the troops may ultimately shift their loyalty to the manager who conducts their performance evaluation, decides their increases and determines promotions.

The truth is that collectively within an organization, while the CEO might be the single most powerful individual in terms of influencing the organization, the middle and upper-level managers are the most powerful layer, so if they are not embracing of innovation, they can stifle it fairly easily, no matter what the CEO's and troops' wishes may be.

Rogues

However, we do see in most organizations that there are “rogue” upper and middle managers who buck the trend. They are either passionate about the company or just turned on by the new and innovative to such an extent that it makes sense for them to take the risk and go “all in” in support of massive innovation. We see that typically about one in twenty middle and upper-level managers are of this type. These individuals can be a key to turning the tide, however there is great risk that these mavericks will face such pressure from their peers in an organization that they either stifle their own tendencies, or more likely, leave for an organization where the culture is more welcoming of innovation. By allowing this “weeding out” of the true innovators at the middle and upper-level management layer, the ratio of rogues can drop from one in twenty to one in a hundred or even less.

Summary

Here is a summary of the attitudinal tendencies. Remember, there are always outliers, this model is only meant to help provide understanding around how different circumstances and levels of risk and reward from change influence people differently at different levels.

CEO + Leadership Team

Attitude: Favor innovation that drives up stock price. Often has sense of urgency.

Risk: The risk is not innovating. CEOs must drive growth which usually requires innovation. If the CEO does not drive growth he, and his immediate reports, are likely to be looking for new jobs.

Reward: Even the appearance of innovation (say, an improved product pipeline) can give a CEO room to breathe with a board and investors as it creates optimism. True innovation at the Apple or WalMart level of course creates superstar CEOs.

Troops

Attitude: Tend to be open to the idea of innovation except when it is targeting outsourcing, staff reductions, or automation which risks their job.

Risk: The biggest risk in typical organizations is that “getting involved” with innovation projects might be seen as negative by the middle and upper managers by whom troops are evaluated.

Reward: The rewards are greater job security if innovation is successful as it helps the whole company as well as the ability to better serve customers an

Middle-Upper Management

Attitude: Tend to resist innovation or seek to compartmentalize innovations that do not jeopardize the organizational structure

Risk: The risk is that true innovation might change the organization so completely that their current position or its level of power, budget or scope would be jeopardized.

Reward: The potential exists for a middle/upper manager to “break out” and prove themselves a superstar by innovating. However most innovation requires collaboration with peers and if they cannot find willing partners in their peers their likelihood of failure is so high that the rewards seems unattainable. For middle/upper managers who are naturally inclined towards innovation despite the risks, the rewards are more emotional—they thrive on either improving things, helping their company or being a part of something new and exciting.